We are all hardwired to respond to subtle social cues. Smiles, laughter, yawning — are all contagious. Studies have shown that when we are in tune with others we unconsciously adapt our body/language to be compatible with theirs.

This unconscious mimicry of physical expression tends to invoke a similar emotional or psychological effect: Someone smiles at us and we smile back; their good feeling becomes our good feeling. To test this premise, smile now and notice how it lifts your spirits. (It feels great and it’s also good for you: professor of psychology Barbara L. Fredrickson hypothesizes that positive emotions can help undo the damaging effects of stress.) This mimicry is considered a biological/psychological/sociological foundation of empathy.

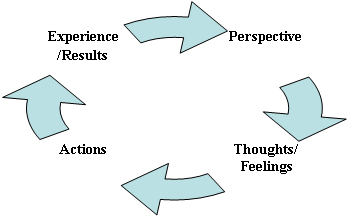

A colleague shared an insight from her own experience. In contrast to her husband, who is outspokenly judgmental, “Barbara” has always kept her thoughts to herself. However, as she has become more aware of her own faults, she had become less judgmental and more compassionate towards others: her perspective changed, and her thoughts and quality of being followed.

Because she had never shared her thoughts, she had assumed that this “internal” shift was completely private, until a family member appreciatively noted how much less judgmental she is “nowadays.” Although she had never said a word, her attitudes had come through in her body language, eyes — her whole presence. And, that had affected the way that people felt around her.

It’s easy to imagine how Barbara’s earlier judgments might have created some subtle or not-so-subtle distance in those relationships, and how this distance would have made it more likely that she would continue to judge and find fault; it can also lead to others judging her negatively in turn: “She is always frowning at me!”

In turn, her new attitude of compassion has clearly strengthened her relationships, creating a more positive dynamic. Although the analogy of dance might be a bit over used today, we might imagine that they are all doing a different dance together. This is about more than feeling good (a good in itself): putting on our practical “ends-oriented” hat, we can also notice that the before and after situations have very different potentials, for example, in terms of what the participants might accomplish together.

Similarly, as leaders, our perspectives and thoughts affect the way we “show up,” the dynamics of the situation, and ultimately, its potential.

This is something we all already “know” from our own experience. However, our cultural emphasis on “doing” often blinds us to how a shift in our perspective (“our being”) can transform a situation in ways that no amounts of “doing” under the old paradigm could accomplish…

Practice

1. Begin to notice how the way other people “show up” affects you, and how you are inclined to “show up” with them.

2. After you have some experience with practice #1, you might begin to notice how differences in the way you “show up” affects others and the situation. A constructive experiment, if you are not already doing this regularly, would be to practice actively looking for the positive in others and notice how it shifts the dynamics of the relationship and situation.

Please feel free to share your experiences here.