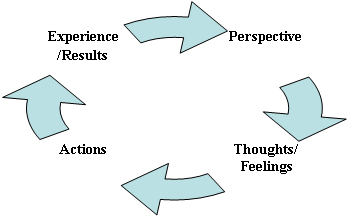

In my last post, we considered how our perspectives can shape the conditions that reinforce our perspectives — how they help shape our realities. For those of us raised in a Western culture, this idea can take some getting used to. Our ideas (and hence experience) about ourselves and the world have been strongly shaped by Newtonian physics (1), which imagines the Cosmos as being built-up from tiny particles — each separate from the other. Consequently, we tend to think of ourselves as essentially separate from each other and the rest of the world, selecting elements of our experience that conform to our belief, and taking actions based on this assumption (including the development of institutions) which tend to reinforce experiences that support this worldview. In this way, we can be seen to substantially build the worlds of our experience. Organizations are one of these worlds of experience.

However, an emerging paradigm, which might be termed the systems view, based on the new sciences, holds that this idea that we are separate — islands, is an illusion. As Einstein famously reflected, “A human being is part of the whole, called by us ‘universe,’ a part limited in space and time. He experiences his thoughts and feelings as something separate from the rest — a kind of optical delusion of his consciousness. This delusion is a sort of prison for us, restricting us to our personal decisons to affection for a few persons nearest to us” (qtd. Laszlo 2007, pp. 50-51).

We both shape and are shaped by the larger Cosmos because we are not separate from it. In the weak form of this idea, there are millions or billions of causal threads that connect us to others, such that they shape us and we them. In the strong form of this idea, the world is imagined as holographic in which each part contains the whole; because we are continuous with the whole, we are each the the totality of the Cosmos, from our unique perspective.

For this reason, the scientific ideal of the objective detached observer can only be approximated: as observers, we are part of the system that we observe. Therefore, both our observations and our responses to our observations affect the system, including ourselves, in gross and subtle ways.

For most of us, this is a really unfamiliar way of thinking about and experiencing the world, and it is more comfortable to make a mental note of it and continue on with our day. Neurologically, our brains tend to prefer the ideas we already have: each time we reinforce an existing belief, we experience chemical rewards. On the contrary, when a settled worldview is challenged, we experience the uncomfortable sense of needing to “find our feet” once again — to reintegrate our knowledge and experience so that we once again inhabit a coherent and integrated reality; it takes energy, work. For this reason, we tend to resist changing our perspective unless/until the old one become too painful or dysfunctional. (No wonder change is hard — no one little thing shifts in isolation: the whole system must adjust…)

For this reason, I don’t want to gloss over this really key idea of how perspective shapes reality (or its complement, that perspective is not the only determinant of reality!). As promised, we’ll continue to look at examples of how this works in practice. My hope is that, as the power and utility of this emerging paradigm of reality for addressing felt pain in organizations becomes more clear, that attraction and pleasure become the stimulus for learning and growth. We still experience the tension of the integration and reconciliation of new knowledge, but it’s now part of a larger, exciting process of discovery…

A big goal — we’ll see how I do 🙂

So, next time, we will continue with the promised topic of how our perspective can draws out or diminishes the potential of ourselves and of others — which is (clearly) key to leadership and organization. This will lead us a discussion of the power of the situation (or structure) and some insights on diversity and creativity. Eventually, we’ll use these various insights to build our Wheel of Freedom …

Notes

(1) I hope you will forgive this oversimplification – if there is time and interest, we can expand on the topic of how our understanding of self and world have evolved, and the areas where culture has yet to catch up with new advances in science – especially “new” physics and biology.

References

Laszlo, Ervin. Science and the Akashic Field: An Integral Theory of Everything, 2nd ed. Rochester, VT: Inner Traditions, 2007.

Newberg, Andrew and Mark Robert Waldman. Why We Believe What We Believe: Uncovering Our Biological Need for Meaning, Spirituality, and Truth. New York: Free Press, 2006.